It’s a strange but undeniable fact that most people do not read websites about Belgian chess history, nor are they interested in blog posts complaining about the representation of chess in popular culture. As a corollary to this theorema egregium, it follows that my website languishes in the barely visited backwaters of cyberspace. But I still have an ace up my sleeve,1 and I’m going to play it now: here is the Internet’s favourite thing!

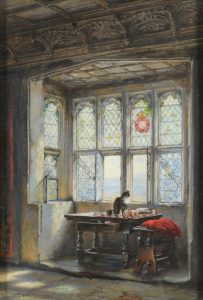

I nicked this image from here and invented my own title, since there doesn’t seem to be an official one. Unless we consider “17th century interior scene with a cat seated beside a window” a title, but to me that’s a description. The painter is apparently a certain Frank Moss Bennett, who made this particular canvas in 1923. I had never heard of the guy before, but I kind of like the few paintings of his I’ve seen. It must be said, though, that my taste in the graphical arts is about as refined as a turnip, so maybe this Bennett is a talentless hack – I don’t know.

Anyway, the scene is quite interesting. There is only one chair, and there is an open book laying next to the board. Unless the cat has been playing, the evidence seems pretty strong that somebody had been studying chess here on his own. This in turn suggests that the book is a chess book – the first one to show up in the CIPC series, I believe.

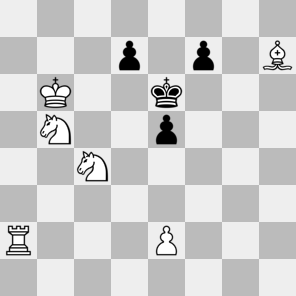

Assuming whoever was at the board looked on from the white side, the position seems to be this:2

I would snort derisively at the non-standard pieces, but in the 17th century these pretty much were the standard pieces. Perhaps they’re even a bit of an anachronism; I don’t really know when the St. George pieces – for that’s what they seem to be – were introduced.

I would snort derisively at the non-standard pieces, but in the 17th century these pretty much were the standard pieces. Perhaps they’re even a bit of an anachronism; I don’t really know when the St. George pieces – for that’s what they seem to be – were introduced.

The position seems to be a strange one. First of all, because the difference in material is too big: white should have been able to force a quick mate with such an advantage. Secondly, the pawn configuration is highly suspicious: the e and d-pawns usually move very early on.

In fact the whole thing looks more like a chess problem. As if there should be a mate in three or something. This is not the case, but in creating the diagram, I accidentally put a white pawn on e5 instead of a black one, and this position turns out to be a non-obvious mate in 4! The pawns on e2 and f7 are superfluous, but in the 17th century it would be a more than acceptable composition. And the ports have names for the sea…

Realism: 4/5 The most likely explanation seems to be that it’s a composer’s work in progress, in which role it’s quite convincing.

Probable winner: In the 17th century there were, as far as I know, no composition tournaments, hence nobody won.

1. [I’ve always found that a rather dubious expression. Doesn’t it imply pretty clearly that you’re going to cheat?]↩

2. [Painted with a broad brush.]↩